Firing Up the Frontlines

BPI’s business continuity plans are on par with the best in the world. But COO Mon Jocson reveals the best battle plans are only as good as the heart of the people fighting at the frontlines

Words by AN MERCADO ALCANTARA

The sudden appearance of a long queue outside the bank was telling a story.

But it was not the scoop business reporters expected. News hounds who bombarded the Bank of the Philippine Islands (BPI) head office with questions were calmly told that the bank was just implementing social distancing measures.

It wasn’t headline news, but it was a foreshadowing of things to come. In those early days of March 2020, the COVID-19 threat seemed distant. Few wore face masks or carried bottles of alcohol in their bags; only a few worried about getting sick. Floor markers and limiting the number of customers inside the branch seemed extreme. But the bank was thinking ahead. Weeks before ECQ was announced, BPI’s pandemic crisis management plans were already in full swing—the queues were just the first visible signs.

“In early February, some of our multinational clients were already asking for copies of our pandemic plan,” reveals Ramon “Mon” Jocson, BPI Executive Vice President and COO. “Most of these multinational clients have their regional HQs in Singapore and Hong Kong where the governments were already instituting quarantine measures.”

Mon chairs BPI’s Crisis Resiliency Committee (CRC), the management group tasked to assess crisis situations and trigger the bank’s continuity business plans. Before joining BPI in 2015, he spent most of his professional life as part of the leadership team of the multinational tech giant IBM, where in a span of over 30 years, he took on operational responsibilities in Asia Pacific, Central and Eastern Europe, Latin America, Africa and the Middle East. In fact, he was working in Singapore in 2003, when there was a large outbreak of SARS.

“I managed IBM’s global services for ASEAN and South Asia,” he recalls. “Some of my clients were a multinational bank, a premiere international airline, one of the Singapore government’s ministries and many more. I remember during the first few weeks, all I did was assure them that we were behind them.”

Mon Jocson

That is, in fact, the cornerstone of a sound business continuity plan (BCP) — the assurance that, no matter what happens, your company will still be there for your customers.

Responding to the urging of their international clients, the CRC anticipated the unfolding of a crisis and convened in February, weeks before the World Health Organization declared a COVID-19 pandemic. Mon asserts: “To remove customers’ doubts, the speed of decision-making is very important.”

By acknowledging the crisis, shepherding of bank operations was turned over to the Committee, which includes BPI President and CEO “Bong” Consing and all senior executives of the bank. In what became weekly Tuesday meetings over WebEx, forty Committee members would log in at the same time from different locations, all tasked to carry out the Bangko Sentral-approved business continuity plans.

There was a briskness to these virtual meetings. Mon himself says he doesn’t believe in long discussions. “The problem is sometimes people can analyze too much,” he explains. “We shouldn’t let perfect be the enemy of the good. People in the field look for immediate guidance. But I was also fortunate to have Marita Socorro “Mayette” Gayares, our Chief Risk Officer, as co-chair of our CRC, as she tempered my bias for action with prudence and completeness.”

It helps a lot that the members of the committee have become veterans at crisis management. In the last three years alone, they’ve had to pull out their BCP for floods and typhoons, earthquakes (in Cotabato and Davao), terrorist attacks in Marawi, and most recently the eruption of Taal Volcano in January. The three-step decision process was well oiled—Stage 1: Ensure everybody is safe; Stage 2: Get together for plans of action; Stage 3: Communicate to key stakeholders—customers, employees, regulators and the general public.

Banking in the New World. In an interview with ANC, Mon Jocson describes BPI operations during the lockdown, and how it is pivoting into the New Normal as more banks reopen under Modified Community Quarantine. He also observed a general shift in consumer behavior, noting a 200% increase in digital transactions. “In fact, 90% of our transactions now are done through the digital channels.” (“Banks Adapt to the New Normal.” ANC, 14 May 2020, https://youtu.be/8zVE0SEhWZQ)

The BCP had clear guidelines for how to handle a pandemic. In January, health advisories were already sent out to employees. Masks, acetate guards, and social distancing guidelines were provided by February. Coming into March, the Committee had a good rhythm going. A few of the sweeping decisions made were to create safety pockets so that all the bank’s critical functions could run even if some employees were to contract COVID-19. They decided to split specialist teams, have units of bigger teams swap locations, move subsets of the head office units to alternative sites, and have a pinch-hit system among bank branches in case one has to close down. They felt confident that they could operate even as they tried to contain the possible spread of the virus within the organization. But Mon admits: “One can never be fully ready because each situation brings a different dynamic.”

On March 16, when the entire island of Luzon was put under lockdown, it threw a monkey wrench into their plans.

AS CEO Bong Consing would reveal in a letter to clients: “Having prepared for two months, I thought we were as ready as we could be for the government’s implementation of the Enhanced Community Quarantine (ECQ) to fight COVID-19. But the ECQ presented some unexpected challenges… The comprehensive lockdown revealed the limitations of our planning.”

What their best laid-out plans did not anticipate was the halt of public transportation, the skeleton force guideline on staffing, and the effect of an inter-island travel ban on cash reserves. These were beyond the scope of the BCP. As prepared as they already were, the Committee now had to test their mettle on new battlefronts.

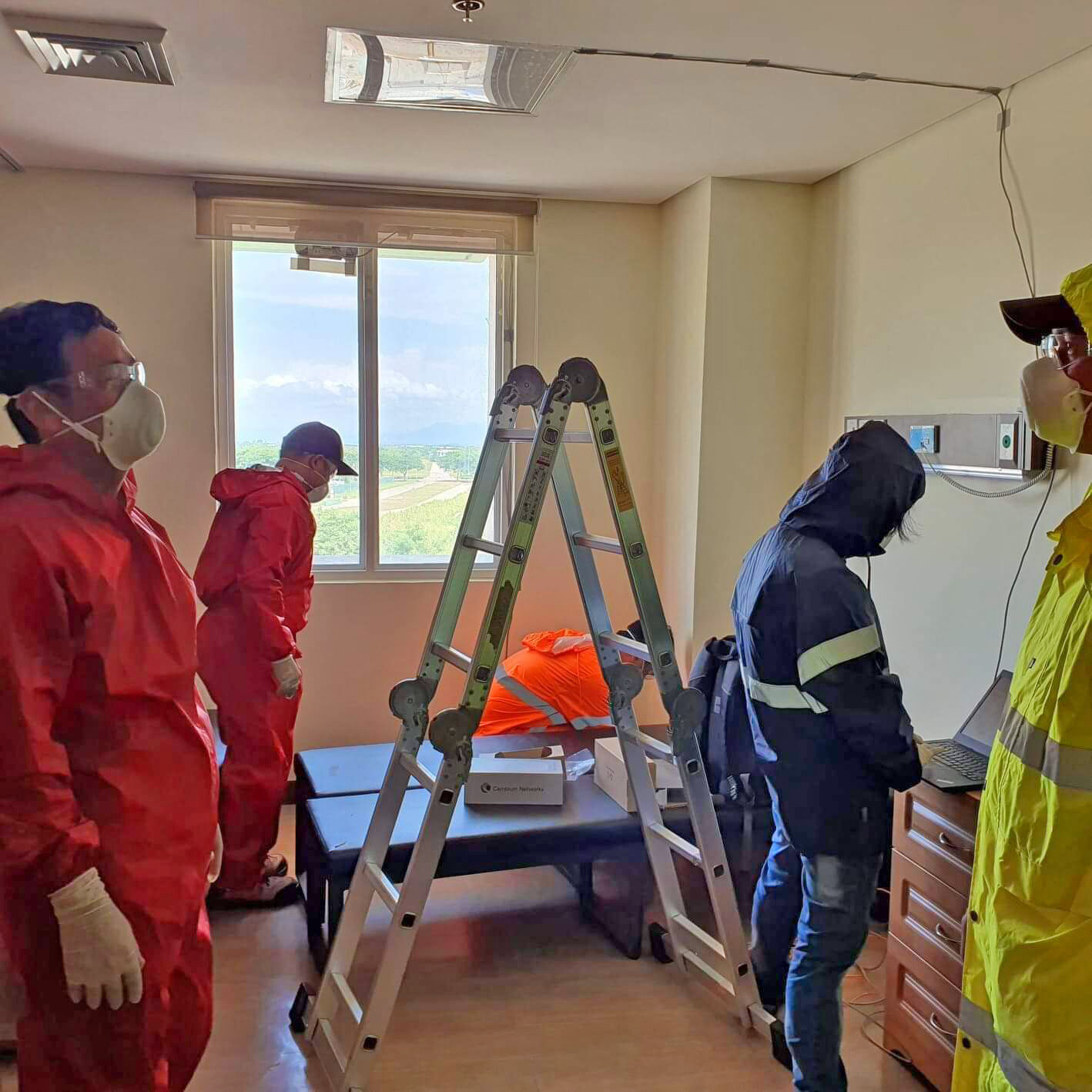

Crisis plan. BPI’s social distancing efforts were part of a well-planned, company-wide effort to protect customers, employees, and frontliners. All over the Ayala group, business continued in earnest even while the whole island was on lockdown: Globe installed free WIFI and distributed disinfectants to hospitals; BPI used dividers and masks; Manila Water ensured ample water supply for handwashing; and IMI sheltered essential employees.

““What’s important in a crisis is to avoid ambiguity and ambivalence. Be explicit about what you want done and your expectations.””

All over the Ayala Group, similar scenarios were unfolding. Globe’s ISO-certified BCP and their infectious disease control plans had to be adopted quickly to keep the telecommunications backbone running even as lockdown restrictions affected their logistics chain. AC Industries had to meet their global manufacturing commitments and find ways to protect their factory workforce. Manila Water and AC Energy had to make sure water and energy flowed uninterrupted even as daily life came to a standstill. While most hunkered down at home, many Ayala citizens had to rush to the frontlines.

Cash flow. BPI frontliners hurdled both physical and metaphorical roadblocks to keep ATMs filled with cash—and even made sure they were properly disinfected.

An ATM’s cash journey traces the bloodstream of the economy.

No matter what, and against all odds, cash deliveries must always continue to flow. For BPI, supplying cash to its vast network of ATMs became a matter of national economic importance.

“We are delivering essential services to the country,” Mon explains. “If ATMs are not filled, then financial transactions are hampered. We will be at a standstill.” But under a lockdown, managing the circulation of money became quite tricky.

In ordinary circumstances, the journey begins and ends at the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP), where armored truck and security service providers pick up cash and bring back deposits on a daily schedule. Highly trained, armed security personnel routinely carry out the prompt and secure movement of cash. The logistics chain is both simple and sophisticated, pulled together by a set of assumptions easy to expect in normal times, but suddenly pulled out of the equation under quarantine restrictions.

The first assumption to fall away was the daily round of cash pick-ups. In the early days of the ECQ, the BSP limited cash ops to only three days a week. That posed a big problem. The cash supply was choked at the source. Without the mother ship to rely on, banks looked to each other for help. “We started calling other banks,” Mon recalls. “Our Central Operations Group Leader, Gene Mercado would ask: Do you have extra cash? Palitan tayo.” The other banks quickly agreed. By borrowing cash for delivery and then returning deposits for replenishment, they effectively created their own little supply chains.

““To remove customer’s doubts, the speed of decision-making is very important.””

The second links to disappear were the availability of armored transport and their ability to move about. Because public transport was grounded, many in the security teams just couldn’t get to work. So BPI deployed their own teams. On their mission trips, unexpected roadblocks and frequent stops at checkpoints dangerously slowed down their progress, but the teams kept moving.

But not all blocks were physical barriers—some were invisible. The Crisis Committee kept a close eye on cash levels at ATMs in hospitals, where a surge in demand was expected and cash needs were sometimes a matter of life and death. Cash deliveries had to be constant, but the armored vehicle crew feared that going into hospitals would put their own people at risk. Discussions ensued, with the BPI team rallying their partners to join them in their mission to help those in most need. Owen Cammayo, BPI Corporate Affairs and Communications Head, recalls: “Fortunately, the service providers realized the importance of supporting our front liners, as well as the patients who needed cash. They provided their team with PPE, alcohol, gloves, and other sanitation tools to safely service the hospitals.”

The third weak link was triggered by practical decisions, made by millions of people who were withdrawing cash but keeping them in their households, holding on for emergencies. And because most businesses were also closed during the lockdown, the cash cycle thinned out.

“Banks are in great shape,” Bong assured customers through a television interview on March 19, “The real issue is the physical cash. We just have to make sure that we get physical cash to the branches and to the ATMs.”

Unbreakable. Bong Consing, speaking as the president of the Bankers Association of the Philippines, says he remains confident in the country’s ability to recover from the economic aftershocks of the pandemic. (“Can PH banks handle loan extensions, brace for more COVID-19 disruptions?”ANC, 30 May 2020, https://youtu.be/ZodDKu8ajdk)

But getting physical cash to other Luzon islands would prove to be most challenging. The fourth logistics loop to vanish were air and sea transport services. “PAL used to run daily to carry our cash. Suddenly, there were no flights,” Mon recounts. “So what do you do?” Again, the Committee bridged the gap by joining forces with their fellow banks. Together they chartered a plane to get the bank notes to Puerto Princesa City (which had already run out of cash). For Puerto Galera in Mindoro, where cash transport was usually done through roll on/roll off vessels, the bank had to charter a boat.

Ultimately, they had to spend money to transport money. The level of cooperation between banks just to ensure that cash continued to flow was unprecedented. Bong, who is also the president of the Bankers Association of the Philippines, said in a letter: “Fellow bankers, ours is a mission critical industry. What we do and, equally important, what we choose not to do, will help shape our nation going forward.”

Continue to serve. The Makati Stock Exchange branch was one of the 198 BPI branches and 33 BPI Family Savings branches that remained open during the lockdown.

When Mon entered the BPI Command Center, his eyes quickly darted from monitor to monitor.

Given an imposing Big Brother view of various branches and offices nationwide, he scanned quickly for long queues and to see if employee safety standards are being followed. All through the ECQ, he has been coming to work every day, often shuttling between this Command Center, where he has central view of brick-and-mortar branches, and the Cyber Security Center, which monitors BPI’s online banking channels and the online footprint of the company. “I have to see all that’s happening,” he says. “It’s hard to do that from home.”

On this visit, he kept a close watch on 25% of all Luzon branches—these were the only ones allowed to open under the ECQ. On March 16, when the branch limit was announced, the Committee had to convene to quickly map out which branches could help the most clients. They used data analytics, the sound judgement of people on the ground, and geographic information. And then they looked closely at staffing. “We defined cells,” Mon explains. An area would have three teams. “If one team gets infected, that team goes off line, then you go to Team B, then Team C. You close one branch, open another.”

Culture of Malasakit. BPI frontliners not only volunteered for the job, but helped each other out—organizing carpools, or even sheltering co-workers who lived far away.

““People were raising their hands to come to work—to be part of the 25% in the frontlines.””

The open branches became mission stations in vast empty cities. Volunteer staff were pulled out from their regular areas to join others in the central branch. For those who relied on public transport, teams organized carpools or found alternative places to stay. Once in the branch, BPI looked after their safety and needs. “We were one of the first banks to announce that our skeleton force would get daily special allowance and meals,” Mon reveals. Human Resource concerns like these, along with a vigilant watch on COVID-19 cases in the organization, were always priority agenda for him.

The Committee also had to grapple with government guidelines. Every CRC meeting began with an update on the latest quarantine directives. Especially in the early days, many rules had to be sorted out—like what did the quarantine alphabet scramble mean? Did everyone need an IATF ID? Where could one get those? On top of that, each local government unit (LGU) had their own set of rules. So branches in different cities faced different challenges, which the Committee had to look into. From these discussions, they gleaned clear directives for their teams. “What’s important in a crisis,” says Mon, is to “avoid ambiguity and ambivalence. Be explicit about what you want done and your expectations.”

Although he could see all branch activities and get constant reports from the safety of the Command Center, Mon insisted on visiting branches. Belonging to a family of doctors, he took precautions and acted as a front liner. “At the end of the day, you cannot be in command without going out there,” he says. “Leaders need to be seen. You can't ask your people to meet with clients every day, then not risk it yourself.”

In his rounds, he rallied the troops and looked closely at how the branch was keeping them safe. And, equally important, he met with customers. If there was a long queue, he asked what they needed, and offered an alternative. “You don’t have to line up. You can do it in the BPI Mobile app.” He’d even fish out his phone and do quick demos.

Financial freedom at your fingertips. The BPI app allowed customers to view accounts, transfer money and pay bills from the comfort and safety of their homes.

At a branch in Pasig, he encountered a middle-aged woman who, after waiting patiently in line, had to be turned away because her thermal scan showed she had a fever. She was distraught—she had a small buy-and-sell business, and needed to withdraw money to buy supplies. Without cash, she’d be out of business. Hearing her story, Mon said: “Diyan lang po muna kayo. Papalabasin ko po yung branch manager and we will handle your business out here.”

Mon recognized that in the time of strict quarantine, it was an act of bravery for clients to be out there. They had to match that with safety, yes, and also with efficiency and kindness. As Bong said to fellow bankers, “Stand by your posts! Even if your jobs require person-to-person contact, especially in the branches… Care and courage — these must be our bywords.”

““What we do and, equally important, what we choose not to do, will help shape our nation going forward.” ”

Digital Frontline. In March and April, when lockdown was most strict, a whopping 90% of BPI’s bank transactions were on digital platforms. BPI’s Crisis and Resilience Committee monitored activities closely to make sure all channels were able to carry the increased capacity. At the BPI Cyber Security Operations Center, state-of-the-art sensors created a wall of protection around their digital systems.

From the start, the Committee knew that care and courage could not be imposed from the top. They decided nobody would be forced into the frontlines. Because of the risks, people had to be free to choose. They needed only 25% of the branch workforce to volunteer and be counted, but Mon feared he would not get enough. “What really inspired me was we got more volunteers than we needed,” Mon recalls. “People were raising their hands to come to work—to be part of the 25% in the frontlines.”

What moved him even more was many of these volunteers eventually chose to donate their special allowances to COVID-19 charities and the efforts of BPI Foundation. For them, being in the frontlines wasn’t about the money.

“That’s malasakit,” Mon says. “It’s culture that is essential in times like this. Because we have common values, people go out of their way to make sure that the outcome we expect happens… They truly believe that banks are essential to delivering services to the country and that each one of them has a role to play.”

Beyond BPI, the need to serve was also firing up the front liners all over the Ayala Group—risking to care, pushing fear aside to keep all vital systems running. When people bring their hearts to it, an efficient BCP becomes a platform for heroism. #

This story is part of a series on how Ayala citizens worked at the frontlines to ensure business continuity through the pandemic crisis. Want more? Check our related stories: Slumber Party with the Lady Boss, Calling From the Heart, and Superpowers of a Lineman.

POSTED JULY 31, 2020