Breath of Life

How two engineering ‘geeks’ took a groundbreaking design for a modified, cost-efficient, life-saving ventilator to fight COVID-19—and built it in the Philippines

Words by ALYA B. HONASAN

THERE’S one more job title that Luke Mendoza, head of Advanced Manufacturing Engineering (Asia) for Integrated Microelectronics Inc. (IMI), can add to the many that he has held: “I was the guinea pig,” he says. “I was the first person they tested it on.

“It didn’t work at the start,” he continues. “I felt dizzy, and we figured it was because too much oxygen was going into my blood. But when it finally worked, it felt very rewarding: ‘Hey, we did it!’ And that was the first unit.”

Luke Mendoza

That unit was the first locally assembled prototype of the UCL Ventura Flow Generator, a Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) system, built by IMI from a design licensed by the University College London Hospital (UCLH) in the United Kingdom and Mercedes-AMG High Performance Powertrains (HPP), for use in COVID-19 cases. It is, scientists have declared a device that can keep COVID-19 patients out of intensive care, and possibly save their lives.

From a logistical standpoint, Luke recounts, a solution was needed that could be assembled in the quickest time possible. “Ventilator” is actually a broad term, he explains. “The hospital ventilators as people know them are actually only needed when you intubate critical patients, which is in less than 10 percent of all COVID cases.”

“From a logistical standpoint, Luke recounts, a solution was needed that could be assembled in the quickest time possible.”

In fact, invasive mechanical ventilation, which means inserting a tube into a patient’s windpipe to push in oxygen, can be traumatic to many patients, which is why it is a last resort for the critically ill.

A CPAP device, meanwhile, doesn’t require intubation. “It’s low-cost, completely mechanical, quick to market, and addresses most of the patients,” Luke says.

A domestic product

The search for a life-saver began when University College London (UCL) critical care consultant Mervyn Singer reached out to Tim Baker of UCL’s mechanical engineering arm, in search of a modified CPAP device. Baker, in turn, contacted engineers Andy Cowell and Ben Hodgkinson at Mercedes AMG. A mere 100 hours later, the crack team of doctors and engineers had their first prototype.

Enter Nick Davey, chief technology officer (CTO) for IMI and IMI’s UK-based subsidiary, Surface Technology International (STI Ltd.), where he had set up research and development. STI had already been working with a few companies on new ventilators and other products that could be built quickly for COVID-19 patients. “So we’d already made some 5,000 full ventilators for Penlon at STI, but for the Philippines, Art Tan told us that we desperately want to offer a domestic product.” Arthur “Art” Tan (ART) is chief executive officer of IMI, and also headed an in-house top management COVID-19 task force convened as early as the first week of March.

Nick Davey

“In the UK, they found that 60 to 70 percent of patients put on the CPAP went on to full recovery,” says Nick. “So addressing this application at the early stage actually prevents people from needing ventilators.” He worked closely with the UCLH team, and the UCL Ventura Flow Generator has already been approved by the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) for use in their country for use within the COVID-19 pandemic period.

After the design and manufacturing instructions were made available for free, Nick signed IMI’s license agreement to manufacture the UCL Ventura Flow Generator in the Philippines. “A ventilator could cost upwards of $10,000. This device was about $3,900. Some governments don't have $100 million dollars to spend on ventilators, but they might have $10 million, and that's why this solution was beneficial—it was cost-effective, and we could certainly see the positive results of its use.”

Back in Manila, Luke credits Art for “making things happen quickly” so IMI could be at the forefront of innovation. “We had already looked at 14 different ventilators, half of them local, and our original intention was to help people industrialize their designs quickly, because we have the infrastructure for manufacturing. At the same time, we were getting inputs from Nick from the task force in the UK. We had meetings with all the designers and consultants, and internally we did our own analysis, our own due diligence.”

““Some governments don’t have $100 million dollars to spend on ventilators, but they might have $10 million, and that’s why this solution was beneficial.””

Small but powerful. Up to 70% of patients who go on CPAP don’t need to go on ventilators—lowering the patient’s discomfort, risk for infection, and hospital bills. It is the first ventilation system to be produced in the Philippines, and has been approved by the FDA.

Global collaboration

Thus, followed what Luke called “a global collaboration, because fortunately, we’re a global company.” The Filipino production team was in Laguna, with Singapore providing global logistics for parts not available in the Philippines. IMI’s US and China factories helped source the delicate precision materials required. IMI also worked with the Institute of Biomedical Engineering and Health Technologies (IBEHT) of De La Salle University (DLSU).

Having Nick keep in touch with UCL facilitated the process, Luke says. “He was instrumental in making sure we had access to the people who could answer our questions, so we were able to make adjustments immediately.

“It’s a very simple design, in that there are few components,” Luke continued. “However, it required precision tools and machining, because it was designed by a Formula 1 team; it was that kind of technology.”

The Philippine prototype was built in the IMI factory in Laguna. “ We were on lockdown, so we had to transport people from their homes,” Luke says. “I think seven people had to come in, and literally had to sleep and eat in the factory compound.”

““You are doing something that your life and the lives of the people around you depend on—that’s what drove us.””

Working from home

Luke himself was surprised when the work was completed in only three weeks. “It was a long three weeks, though, as we were working day and night, making calls.” This was accomplished with key players working from home, until he headed to the factory for the aforementioned testing.

Last May 19, IMI and STI Ltd. introduced the UCL Ventura Flow Generator and organized a series of webinars, what they called “virtual consultative and information-sharing sessions with medical experts, health practitioners, and concerned government agencies.”

“We were quite pleased with the participation we got from the doctors, from the Department of Health,” says Nick, the webinar’s main speaker. “It was specifically a Filipino audience, and we wanted a forum which allowed people to ask us the difficult questions, to help alleviate some people's fear of CPAP being the right solution.”

Three months later, in August, IMI officially received certification from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the device. Thus, allowing the company to support the government’s call for local outsourcing and manufacturing of low-cost ventilators and other breathing aid solutions in caring for COVID-19 patients.

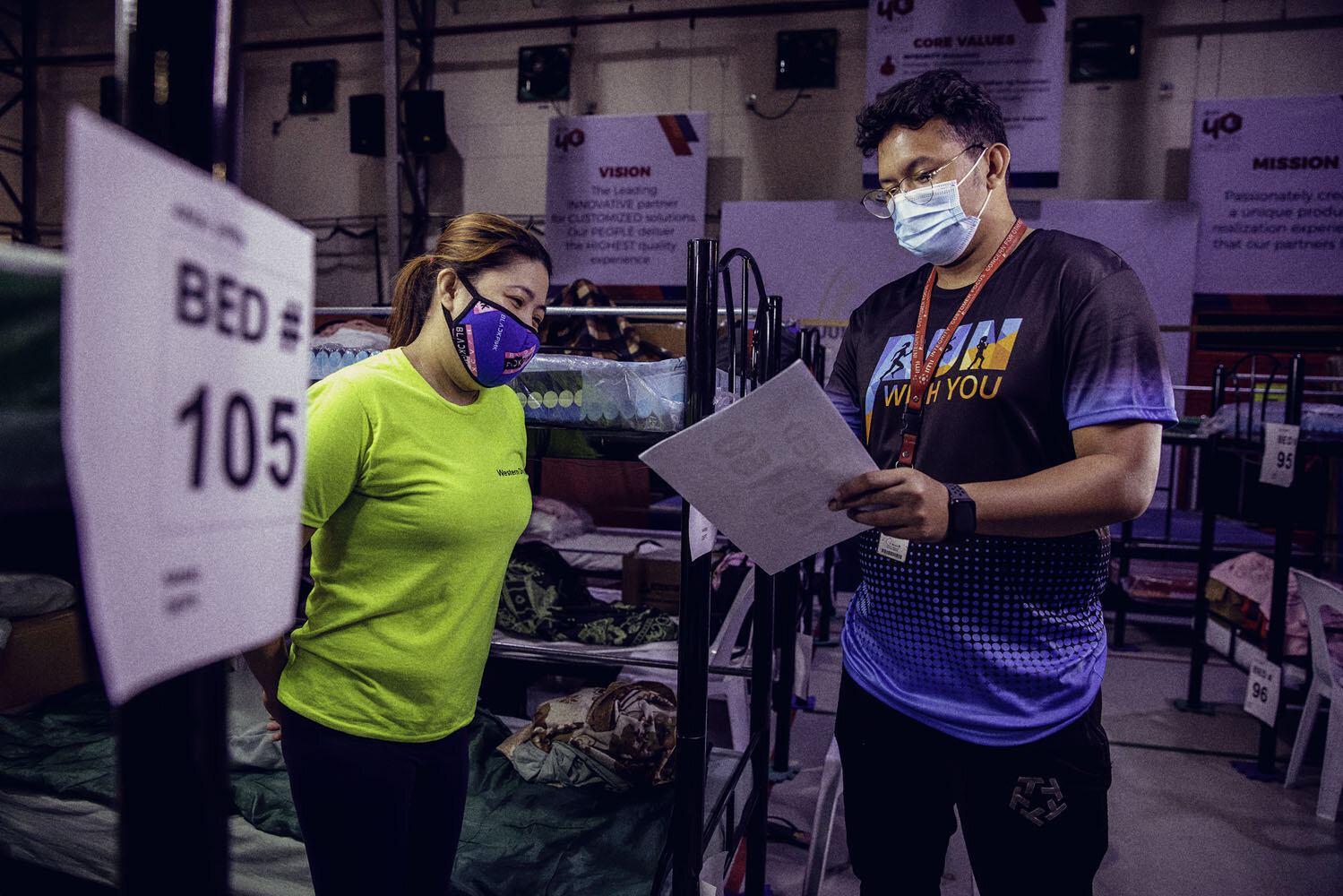

#AyalaCitizen Diary: Strict safety protocols protected the team working on the UCL Ventura Flow Generator, who were among 1,300 IMI workers sheltered in the factory during the lockdown. (Read more in “Sheltered.”)

They’ve come a long way

Nick and Luke have known each other for three years, like-minded colleagues in a dynamic industry. “He was handling design and development for STI, and I was handling the same as well as advanced manufacturing engineering for IMI, so we were counterparts,” recalls Luke, an electrical engineer who admittedly “loves to tinker,” and is now a full-time IMI consultant; he recently retired after spending 30 years with the company. “As peers, we’d talk about R&D, technical stuff—geek talk. It was a natural bond because we have a lot of things in common.”

“Luke is one of the guys at IMI whose guidance and knowledge I look out for, for his experience and his engineering capability,” Nick says. “Luke and his team were the glue that brought this all together.”

Technology that saves lives. Fernando Zobel de Ayala, who is also chairman of AC Health, inspects the UCL Ventura Flow Generator during a visit to the factory. “Healthcare is one of the many sectors that has been disrupted by this global crisis. However, I believe that many of the problems caused by COVID-19 can be addressed by technological innovations. The Ayala Group is determined to meet this challenge by leveraging the talents of our own engineers and medical experts, and by pioneering digital solutions,” he said in an the announcement of the company's support for frontliners.

““Technology will play a massive part in the future of the world. I never would have thought we would be able to manage this during a pandemic.””

Nick had been with STI Ltd. for 10 years, but took on the role of CTO for both STI and IMI only last January. Being sidetracked, as it were, to focus on one specific life-saving machine may not have been expected, but “the sense of satisfaction is immense,” says this father of four daughters, one of them an emergency dispatcher with the UK’s National Health Service. “Technology will play a massive part in the future of the world. I never would have thought we would be able to manage this during a pandemic. Also, every day I wake up to messages from ART, JAZA and Fernando heading our teams, meeting our people, supporting our frontliners. That’s all the inspiration you need,” referring to Arthur Tan, CEO of IMI, Jaime Augusto Zobel de Ayala, chairman and CEO of Ayala Corporation, and Fernando Zobel de Ayala, president and COO.

For Luke, a senior citizen considered “high-risk” during the pandemic, the fact that “you are doing something that your life and the lives of the people around you depend on—that’s what drove us. We have an incredible team. We don’t have medical experience, but in the span of two months, everybody learned. We now jokingly call each other ‘Doc.’ We were all responding to the same global emergency. So yeah, it was a fantastic experience.” #

PUBLISHED SEPTEMBER 11, 2020